By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

December of 2006, I was in Germany unable to come back to the States. Now, lest you think I was in trouble with the State Department, the reason I was there was that as a Foreign Service Worker, I had to stay out of the country 335 days of the year, and this was one of two times in the three years I was in Baghdad that I could not come home for leave. So, I went to Germany to spend my R & R with soldiers who had become like family to me while in Iraq, and as odd as it might sound, one of the most impacting moments was going to Dachau, the infamous Nazi concentration camp. Dachau is well-known for a number of things: ovens in which people died, documented medical experiments, and people, one of whom changed the world by coming out of Dachau better than when he went in. His name was Viktor Frankl.

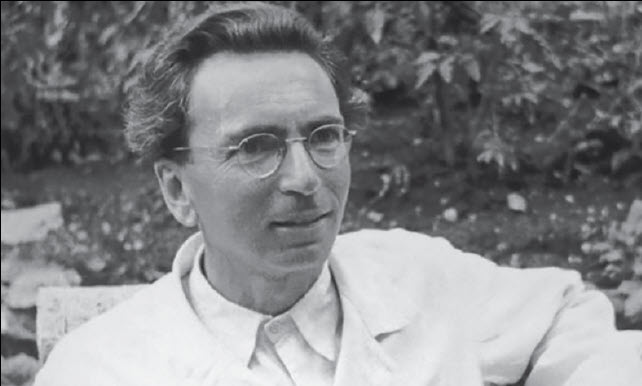

Frankl was a Jewish psychotherapist from Austria, and during WWII he was in four different concentration camps, including Auschwitz and Dachau. He experienced untold tragedy, including being forced to abort his child, losing his wife and parents in the Holocaust, and enduring the Holocaust himself. In 1946, metaphorically while the ovens were still smoking, he published a book whose title eventually came to be Man’s Search For Meaning. It was an international bestseller, was translated into dozens of languages, and remains one of the most important books of the 20th century. He wrote a total of 39 books, but this one is his most famous.

Interestingly, before Frankl ever was imprisoned, what rankled people like Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler was that Viktor insisted that there was no more powerful motivator in humans than to find meaning in their lives. He developed an approach to psychotherapy called logotherapy, which has three basic tenets that center around the search for meaning. He says we can find meaning by:

1. Creating a work or doing a deed

2. Experiencing something or encountering someone

3. By the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering.

He also asserts that “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

With entire industries banking on people never going on the pursuit of meaning and being dedicated to permanent victim status, often the above falls on deaf ears. However, recently a man who was involved in publishing my book, and who is himself Jewish, posted something on Facebook that is another of Frankl’s quotes — one I had never heard, and one that breaks the above three points down into a very simple but weighty phrase: The meaning of life is to give life meaning.

Together they make sort of a “which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg” type of concept; but especially for believers the idea that we cannot ever have our purpose taken away from us unless we allow it is both challenging and comforting. To be sure, I fail often in the course of this pursuit, but as spring, Passover, and resurrection will be here soon, in a whole new way I am committing to give life meaning. I guess another way to say it is, “If Viktor can do it, then I can, too.”

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner