By: Eric Betts

By: Eric Betts

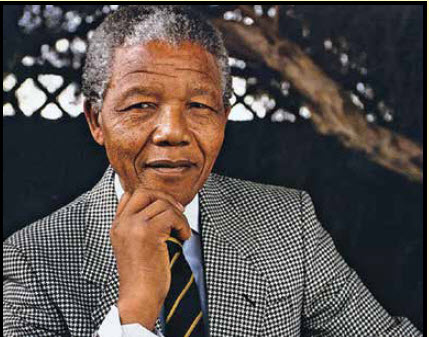

This past week, April 26-29, marked the 29-year anniversary of the first “one-man one-vote” 1994 election in South Africa which made Nelson Mandela its president. Nelson Mandela, the great South African freedom fighter, spent years on the run from the apartheid authorities and 20 years as a political prisoner on Robben Island off the coast of Cape Town.

Mandela began his formative years as an adoptive son of an African king who was also his kin. His perseverance, leadership, and political skill, combined with what he learned in the royal household, helped bring down the walls of apartheid in his homeland. In his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela draws upon first-hand accounts of regional council meetings led by his adoptive father. Mandela observed the proceedings and recognized that the most important attribute of a leader is the capacity to patiently hear all competing perceptions, opinions, and visions without allowing one’s emotions to dominate due to criticism. Because of this frame of reference, Mandela carried this learning experience with him as he was confronted with various competing opinions and agendas during the struggle for freedom. He also used this reference point in his life to lead a multiracial society into a new era after the fall of apartheid.

Toward the end of Mandela’s prison sentence, while living in isolation in a halfway house, he felt compelled to meet secretly with the leaders within the South African government. Neither those within the housing compound where black political prisoners were being held, nor the various factions outside of prison were willing to talk to the political leaders within the apartheid regime. The apartheid regime in South Africa was cruel, oppressive, murderous, and racially dehumanizing, and to communicate with its leaders would be tantamount to betrayal in the eyes of most freedom fighters. The apartheid regime, according to Mandela, did not want to talk to those in the freedom struggle because it would appear as if they were giving in to the political unrest. Mandela believed there was hope despite the stalemate and hostility between the apartheid regime and those in the freedom struggle. Since it was considered unacceptable to be seen communicating with the apartheid regime, Mandela chose to approach them in secret through letters. After the secret communications, Mandela was able to break ground with the apartheid leaders; they secretly met together. They already knew that the regime would not endure due to political pressures internationally and rising sympathies around the world for the freedom struggle. Their greatest fear was that the white minority would be subject to the same treatment that the regime had inflicted on the majority. This communication helped to assuage such fears and to set the terms for their discussions.

What we learn from Mandela’s model for conflict resolution is that to deal with conflict constructively, you must have the ability to speak directly to the person with whom you are having a problem. Without this level of direct communication, the stalemate might have continued much longer. Mandela noticed that direct communication humanizes those with competing interests in the eyes of both parties. When communication is lacking or absent between opposing parties, it is easy to vilify, label, and demonize. Direct communication helps alleviate such misinterpretation and misperception. Mandela, while in prison, found signs of hope when he observed the smallest acts of normal human interactions by the prison authorities toward him. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr observed the same when he said the following: “We must recognize that the wrong we’ve suffered doesn’t entirely represent the other person’s identity. We need to acknowledge that our opponent, like each one of us, possesses both bad and good qualities. We must choose to find the good and focus on it.”

This is the view that Mandela held as he approached the government leadership. He recognized that the time was right for direct communication. Mandela decided to be the bigger person and to take the lead through private communications. This would be the way to work around the concerns about perceptions of weakness and betrayal. He said someone from “our side needed to take the first step, and my new isolation [within the housing compound on the mainland] gave me both the freedom to do so and the assurance, at least for a while, of the confidentiality of my efforts.” It was after the success of the confidential discussions that public negotiations began, and finally, President de Klerk decided to sign the Record of Understanding at an official summit. This set the foundation for all the subsequent negotiations.

Mandela listened to the fears and concerns of the regime figures which opened the door for them to listen to the concerns of those who were being oppressed. They found that retribution was not the goal of Mandela’s African National Congress, but they simply wanted freedom as human beings on Earth and no longer treated as inferiors. Once the terms of the elections were agreed upon, Mandela ran for president under the slogan, Building a Better Future for All. Mandela reassured white audiences that they would not be deported or ostracized but treated as citizens with equal rights. Mandela, while assuring voters that he favored a multiracial democracy, did not mince words in condemning the horrors of apartheid. Both Mandela and de Klerk would later be jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their peace negotiations.

Some questioned how Mandela could receive an award together with one whose policies caused so much pain. Mandela responded by telling the story about how he managed to balance criticizing de Klerk in the negotiations and appreciating his indispensable contributions toward peace. Mandela explained that at the minimum, de Klerk had the courage to confess that a horrible evil had been committed in South Africa through apartheid and decided to focus on this positive aspect of his humanity. So many in the regime would not be willing to acknowledge this. He also stated that it would not have been strategically wise to weaken de Klerk or undermine him in the process because it would have the effect of also weakening the negotiation process which was in the interest of all. Mandela stated, that “to make peace with an enemy, one must work with that enemy, and that enemy becomes a partner.” Despite hard disagreements and even accusations, Mandela maintained the channel of communication among the parties. The traits of being an active listener, the ability to empathize with the fears of those with competing interests, respecting the humanity of those who are in opposition to one’s values, while not compromising one’s honesty, values, and convictions is greatly needed in our times. Mandela’s faith in humanity and commitment to truth stand as a model for all.

By: Eric Betts

Assistant Director, Curtis Coleman Center for Religion Leadership and Culture at Athens State University

June 20, 2025

June 20, 2025