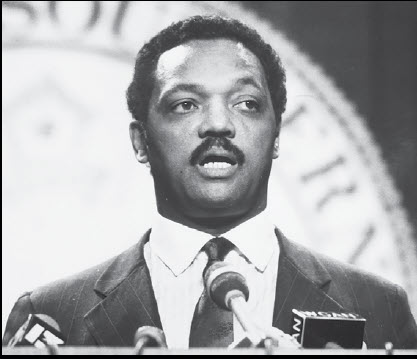

The passing of a notable and historical civil rights icon Rev. Jesse Jackson invites leaders to pause and consider what it means to rise from humble beginnings and still carry a global vision. Born in the segregated South, Jackson grew up in a world determined to tell him he was a nobody. Yet he refused to internalize that lie. His early life—marked by poverty, exclusion, and the daily indignities of Jim Crow—became the soil from which his leadership grew. He learned early that dignity is not bestowed by society but rooted in the sacred worth of every human being. Leaders today need that same grounding: the ability to see themselves clearly, to understand the forces that shaped them, and to refuse the temptation to let hardship shrink their imagination.

Jackson’s accomplishments stretched far beyond the marches and microphones that made him famous. He built institutions, expanded voter access, negotiated international hostage releases, and carried the concerns of the marginalized into rooms where they were never meant to be heard. His leadership was not performative; it was persistent. He believed that reconciliation was not a sentimental gesture but a disciplined practice—one that required courage, proximity, and a willingness to stand for right in hostile spaces. In an era when many leaders retreat into echo chambers, Jackson modeled what it means to step into conflict with a posture of bridge‑building rather than self‑protection.

At the heart of Jackson’s leadership was a simple but radical conviction: everybody is a somebody. He preached it, organized around it, and built coalitions on its foundation. This principle was not motivational fluff; it was a theological claim. To Jackson, human worth was sacred, not situational. Leaders who adopt this posture resist the corrosive pull of hierarchy, favoritism, and transactional relationships. They learn to see the custodian and the CEO with the same clarity. They learn to treat opponents as image‑bearers rather than obstacles. And they learn that reconciliation begins not with strategy but with how we choose to see one another.

Perhaps Jackson’s most enduring gift to leaders is his refusal to relinquish hope, even in situations that appeared hopeless. Whether confronting apartheid, negotiating international crises, or challenging domestic injustice, he carried a stubborn belief that change was possible. Hope, for Jackson, was not naïve optimism; it was disciplined endurance. Leaders today face their own versions of impossible situations—polarization, institutional fatigue, and communities fractured by mistrust. Jackson’s life reminds us that hope is not a luxury; it is a leadership responsibility. To lead is to believe that transformation is still possible, even when the evidence is thin. His passing challenges us to carry that hope forward with the same courage, humility, and unwavering commitment to the sacred worth of every person.

By: Eric Betts

Assistant Director, Curtis Coleman Center for Religion Leadership and Culture at Athens State University