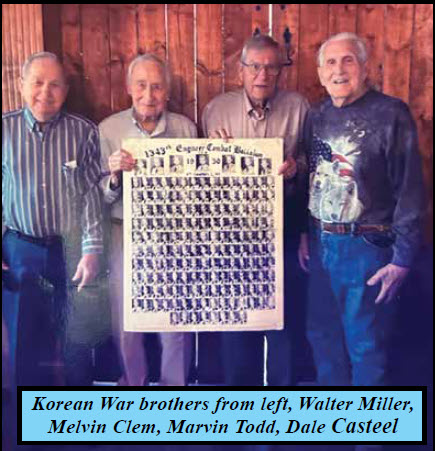

In January of 1951, four young Athenians headed off to the legendary cold of the Korean War. They were Walter Miller, Melvin Clem, Marvin Todd, and Dale Casteel. As is often the case, people who have lived through armed conflict become bonded in a way that is difficult to explain, and that was certainly the case with these gentlemen. Recently, I met with Walter Miller who was 19 at the time he began his military service, and he told me that they signed up as battle buddies with the 1343rd Combat Engineering National Guard out of Athens. Walter attended Athens High School, and Dale Casteel was still in Clements High School. Marvin and Melvin were in their ‘20s. Melvin was in college at the time, and Marvin had finished high school. Walter actually got his diploma from Athens High by going to night school when they returned. They returned in 1952. All are in their 90s now, and Marvin and Melvin are bucking to become centenarians. The total of young men who deployed from Athens with the 1343rd was 142. “There were no deaths, and one lost a leg,” Walter told me. A National Guard member of note in Athens history was Buddy Evans, who served in Korea as a medic. Buddy went on to become many things — sheriff of Limestone County from 1963-1978, coroner for 8 years, and he opened Catfish Cabin and Greenbrier Restaurant.

Backing up just a bit, they trained at Fort Campbell beginning in August of 1950, and headed to the Korean peninsula by boat. The cold that they encountered in the dead of the Korean winter was tough for anyone to handle, let alone young men from Alabama that rarely saw snow that actually stuck for more than a couple of days, let alone a temperature of -42⁰F. “Until it became winter, the weather was a lot like Alabama,” Walter told me. A lot of times the guys were in the same tent, and they worked every day. Their job largely centered around repairing roads and bridges. Previous to the Korean War, the Japanese had cut down all the trees, and Walter mentioned that all that was there were little scrub pines.

I learned something that saddened me, and that is that not only did Korea become the “Forgotten War,” but they were vilified as well. Thankfully it was not as bad as after Vietnam, but Walter mentioned that there were signs posted up North that said, “No dogs or soldiers allowed.” History tends to repeat itself, and I am glad that at least for now, we are in an era where soldiers largely are honored, as they should be.

The fact that all of the 142 came back alive is nothing short of a miracle. They went on to live “regular” lives, and Walter did construction for a few years, and then worked for Amoco for 25 years. “I retired 33 years ago,” he told me. They began getting together for reunions on the decade, at first ten years, then twenty, thirty, and so forth, and had a large reunion of more than 100 that was held at Joe Wheeler State Park. As the numbers dwindled, they began to get together for a meal once a year, and had their most recent reunion back in April. For several years, they kept a ceremonial bottle of champagne. They had an agreement that once it got down to the last two, they would pop open the bottle and toast each other and the rest of the “Korean kinfolk.” Walter told me with a twinkle in his eye that the bottle came up missing, so they replaced it with an unopened bottle of whiskey, and he is the keeper. “But I don’t think any of us actually drink,” he said. Here is a cheer for four men who endured unspeakable cold and more that we might be free.

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner