By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

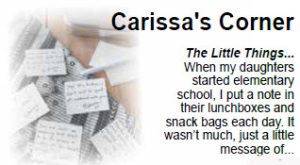

Recently, I experienced one of my favorite things: learning something about WWII history that I had never heard. The source for this edition of Soldier is my friend and Athens Now columnist Colonel Phil Williams, and for one of his daily radio show monologues entitled The Right Side Way, he spoke of what the Steinway Piano Company did for our troops beginning in 1942. They produced around 5,000 of what were known as Victory Verticals, or sometimes referred to as G.I. pianos. Everything about them was ingenious.

The 40-inch uprights were dropped out of B-17s, and were encased in specially designed crates that could handle the shock of the landing while protecting the piano. They were covered first in an anti-insect and especially anti-termite solution, followed by several coats of paint depicting the different service branches and sealed with a special glue to keep them from getting ruined by the humidity of the Pacific theatre or any other weather extremity they might encounter all over the globe. The Army’s “Verticals” were painted olive drab, the other two colors were navy blue and gray. They had no front legs, because they would have broken too easily, and were designed to be carried by four soldiers out of the crate and to the place where they were going to be used. They could also just stay in the crate and have the soldiers come to them.

Of course, this was back in the day when all pianos had literal ivory keys, unlike today, but the keys of the G.I. pianos were compressed celluloid because ivory would have peeled off. In the shipping crate were tools for tuning and various songs of sheet music. One Vertical traveled more than 25,000 miles, and Bob Hope amongst others used them in USO concerts.

Steinway has always been considered the premier producer of pianos worldwide, and it has been common for concert pianists to have their own personal Steinway shipped with them when they are on tour. However, there is only so much abuse a piano can bear, especially when it comes from the bomb bay of a B-17, and here is an affectionate account of the music produced by a well-traveled Vertical:

“Although 88 noises, not all traditional ones, could be elicited from these pianos,” wrote Elizabeth Randall, “what universally characterized them were their sledgehammer touch, the waterlogged tone, stuck keys, missing ivories, squeaky pedals and their scarred, chipped, olive drab exteriors. No offense to the inherent good breeding of these instruments. They had been subject to a few years of tropics and war command treatment.”

As I think about the fact that it is coming up on 20 years ago this summer that I had the privilege of going to Iraq, I am glad that in our Morale, Welfare and Recreation Department we got to bless the troops with music. We had concerts and talent shows, gave music and singing lessons, and the visiting Army bands of all kinds were unbelievably accomplished. From salsa to jazz to marching bands, music did what only music can do: bring joy, comfort, and a bit of home to our well-deserving soldiers, and build community.

God bless the visionaries of Steinway for making it possible for my father’s generation of soldiers to be able to sing and play while they pushed evil back. And, let us remember to do the same in this generation.

“Although 88 noises, not all traditional ones, could be elicited from these pianos,” wrote Elizabeth Randall, “what universally characterized them were their sledgehammer touch, waterlogged tone, stuck keys, missing ivories, squeaky pedals and their scarred, chipped, olive drab exteriors. No offense to the inherent good breeding of these instruments. They had been subject to a few years of tropics and war command treatment.”

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner