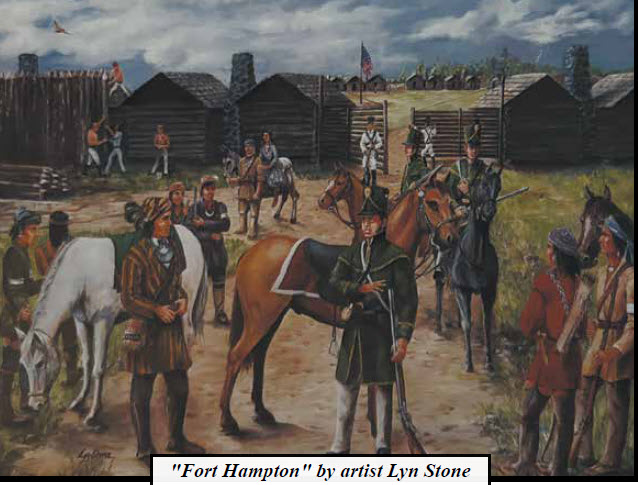

In 1810, President James Madison ordered something that was indeed rare—the building of a fort whose sole purpose was to protect Chickasaw land owners from white squatters. Fort Hampton was built and used for less than a decade in that capacity, and originally had no defenses. This is rather unusual for anything that is described as a fort. If I may wax philosophical for a moment, I find it sadly fascinating that so many of the things that plague fallen humans keep reappearing; ideas such as slavery will be quelled and reappear, and at the moment, on our planet more people are in various forms of slavery than at any other time in human history. Squatting on someone’s land or in their woods makes digital headlines these days, but back when Fort Hampton was built, the problem was apparently troublesome enough that it garnered the attention of a U.S. president in the infancy of our nation, and upholding land rights in this instance was paramount. It is indeed ironic when you consider that Alabama is also famous for being a long portion of the Trail of Tears. However, in this case, without apology, white soldiers removed white squatters from land that belonged to the Chickasaw, and there was never a shot fired between anyone. No outward hostilities were ever recorded, even though the soldiers had to do their job more than once.

The fort was located on a hill overlooking the Elk River near Wright Road. The coordinates are 34° 48.187′ N, 87° 11.913′ W. Its location was chosen because of the literal advantage of “higher ground.” A historical marker is located on Hwy 72 about ¼ mile south of the actual location of fort, which today is on private property. An excavation project occurred in 2013, and the owners were happy to have their land dug up. No human remains were found, but there were things like nails, buttons from uniforms, and logs from former buildings.

As forts go, Hampton was small. It only had 32 log cabins laid out in a rectangle that was approximately 236 feet square. The soldiers were primarily from the Rifle Regiment, and even Sam Houston, who, as part of his legacy was adopted by the Cherokee, served there for a while.

Defensible barriers were added when the War of 1812 broke out, and blessedly, once again they were never needed. In between removing squatters, the soldiers began clearing brush and building the roads that eventually would link Huntsville with Limestone County, and Limestone County to what ultimately became the final borders of Tennessee.

The reason I included this piece of history in a Soldier column is that I am a firm believer in “letting the story be the story.” Just tell it. Don’t try to change it, sanitize it, remove it, revise it, or do anything to it. I am also a firm believer that if you do so, if you let the good, the bad and ugly do their work, you will find something redemptive. In this case, soldiers were ordered by a U.S. president to protect the land rights of the Chickasaw, and they did it. And so, let us honor such actions and protect the story.

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner